«- Back

Where to watch "Light & Magic"

6. No More Pretending You're Dinosaurs

No release date yet

Steven Spielberg sets out to make Jurassic Park with the help of Phil Tippett’s stop motion dinosaurs. But down in The Pit, Steve Williams is secretly building the bones of a computer-generated T-Rex. Muren isn’t sure CG creatures are ready for primetime, but when Williams ambushes producer Kathy Kennedy by putting a walking dinosaur skeleton on one of the ILM display monitors, Muren relents and suggests prepping a test for Spielberg. When the fully rendered T-Rex is displayed on screen for the first time, everyone present knows the world will never be the same. Spielberg describes it as “a religious experience”: “Everything was going to change.” A devastated Phil Tippett can only watch as CG rips away the film that was supposed to be his opus: “My world had evaporated.” But Spielberg and Muren are determined to keep Tippett on board, and utilize his exhaustive knowledge of creature movement. Jurassic Park proves a watershed moment for computer graphics, and in its wake the industry changes rapidly. ILM begins hiring on a grand scale, attracting talent from around the world. At long last, George Lucas feels he finally has the elements he needs to make his long-planned Star Wars prequel trilogy. George pushes the new digital tools to their limit and beyond, much to the chagrin of effects supervisor Knoll, who views many of George’s requests as “marginal, or ill-advised.” George continues to push the industry at large towards digital as well, convincing companies to develop digital cameras and projectors. Though met with tremendous initial resistance, George’s persistence pays off when his proposed changes are gradually adopted. Further validation comes when ILM is awarded the National Medal of Technology. As digital filmmaking enters the 21st century, “just the magic trick on its own is no longer impressive,” explains ILM Chief Creative Officer Rob Bredow. Director and CG skeptic Jon Favreau becomes a convert when he realizes he can no longer distinguish between the real Iron Man suit and the digitally rendered version. Barry Jenkins chuckles at how people think there are no effects on his series The Underground Railroad, which is chock full of invisible effects created by ILM. The innovations continue with The Volume, created for The Mandalorian, which uses gaming engines and motion capture technology to create a large, continuous surface capable of changing locations with a click of a button. With an “eye to the past and an eye to the future,” the powerful legacy of the original Star Wars crew remains alive on The Mandalorian, as evidenced by the practical model of the Razor Crest built by John Goodson, and John Knoll’s pet project of creating a motion control rig in the basement at ILM. As the journey comes full circle, the series ends with collaborators past and present celebrating the deep camaraderie, the spirit of innovation, and the magic of ILM.

5. Morfing

No release date yet

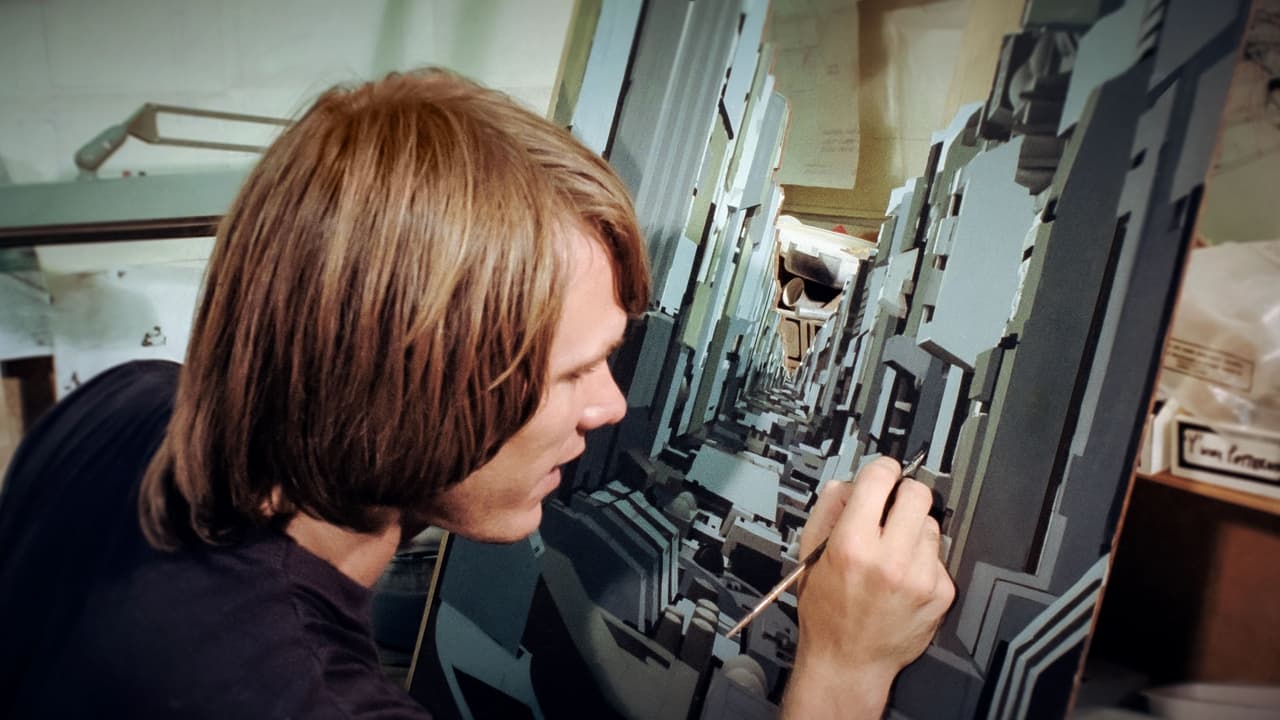

ILM enters the digital wild west as the revamped computer division faces its first big test: a difficult transformation shot in Willow. Furry creature expert Jean Bolte joins the model shop with no idea that her hand-crafted animals will soon be part of a seminal moment in computer graphics history. ILM coins the word “morfing,” which Muren insists is the right way to spell it, claiming, “even the dictionary is wrong.” James Cameron’s new film The Abyss features a realistic water creature that has the director stumped. Muren convinces Cameron to take a “total leap of faith” by making the pseudopod in CG. To pull off the groundbreaking effect, ILM brings in new talent, including Canadian hockey player Steve “Spaz” Williams and Alaskan hippy Mark Dippé, who quickly bond over their mutual love of Alice Cooper. Seeing the writing on the wall, Dennis Muren takes a year-long sabbatical to learn computer graphics, ultimately discovering, “there’s no magic involved… everything can be defined.” Jean Bolte, meanwhile, becomes one of the first from the model shop team to make the transition to computers, seeing the new tools as “just another set of paints and brushes.” But not everyone is ready to embrace the change. Model shop veterans John Goodman and Kim Smith lament that “the joy of working was being together,” physically interacting with the environment, the materials, and each other. General Manager Jim Morris offers training to modelmakers interested in making the move to computers, but Goodman counts himself among those harboring resentment, explaining “they’re taking apart this machine we have here.” New hires are brought in to meet the digital demand, including Ellen Poon, who makes the difficult decision to leave London and her husband behind to move to San Francisco and join ILM. As the computer department blossoms, a new generation takes root at ILM. A soundproof room in the basement becomes Williams and Dippé’s notorious office, The Pit, a hub for wild parties. Cameron returns with a project “a lot bigger than The Abyss,” the “ludicrously ambitious” Terminator 2: Judgement Day, which features a lead character made entirely out of liquid metal. In nine months, the team must create new technology and apply it to the problem. Design pushes the technology through newcomer Doug Chiang’s breathtaking artwork. Terminator 2 cements ILM as the leading computer graphics company in the world, and it is only “a matter of time before we would break out to do something stunning,” says Ellen Poon. That day arrives when Dennis Muren tells the team about their next project, a Steven Spielberg film in which dinosaurs take over a park, with Phil Tippett on board to create the creatures in stop-motion. Despite resistance from Muren, Steve Williams and Mark Dippé view it as a personal challenge to make the dinosaurs in CG. For, as Williams slyly argues, “there’s nothing worse than not trying.”

4. I Think I Found My People

No release date yet

While on vacation together in Hawaii, George pitches Steven Spielberg his version of a James Bond picture, a serial with a “cliffhanger in every reel.” Raiders of the Lost Ark marks the first ILM collaboration with an outside filmmaker. For Spielberg, coming to the Kerner facility feels like entering a playground full of like-minded kids, complete with “really great junk food.” ILM takes home an Academy Award for their efforts on Raiders, but more importantly, they make a lasting impression on Spielberg, who vows “to work with ILM for the rest of my career.” The golden era of ILM’s visual effects begins. Producers Kathleen Kennedy and Frank Marshall recall the joyful work, family-style picnics, and the amazing group of “unpretentious, but brilliant people.” On E.T. Dennis Muren gets bikes to fly. And Richard Edlund’s solution to Poltergeist’s famous imploding house shot involves a miniature house, piano wire, a forklift, and a pair of English shotguns. Ed Catmull’s computer graphics group, meanwhile, creates the Genesis Effect for Star Trek II: The Wrath of Khan, a seminal moment in early digital filmmaking. Collaboration remains king as the ILM crew reunites for Return of the Jedi. Three effects supervisors, Richard Edlund, Dennis Muren, and Ken Ralston, share the workload, but Phil Tippett’s creature shop takes center stage. We also discover how Ralston’s tennis shoe ended up floating in outer space, watch Muren and Joe Johnston create video animatics for the famous speederbike chase, and hear how Muren and Tippett’s longtime friendship extends beyond the Kerner soundstages. Despite success on Jedi, frustrations and burnout abound. Edlund, citing a change in the company culture, leaves ILM. But the rocky time of transition is offset by the string of successes that follow: Goonies, Back to the Future, Cocoon, and more. When Joe Johnston considers leaving the industry, George instead convinces him to attend film school—and foots the bill. Joe credits George’s generosity for launching him into his Hollywood directing career, now entering its fifth decade. For John Knoll, a chance visit to the ILM facilities at the age of fifteen inspires him to pursue a career in effects: “I could be one of these people,” he thinks. “In fact, I think I found my people.” Years later, Knoll lands a job at ILM after building his own motion control system at home. Inspired by Lucasfilm’s Pixar Image Computer, Knoll goes on to help his brother create a new program called Photoshop. Having succeeded in fulfilling George’s digital goals, Ed Catmull remains “hellbent to make cartoons.” Satisfied he now has the tools he wanted, George makes the fateful decision to sell the computer graphics division to Steve Jobs. Pixar is born, as ILM sets to work creating their own computer graphics group, one capable of tackling the enormous challenges to come.

3. Just Think About It

No release date yet

Star Wars inspires a generation of young filmmakers, including countless future ILM collaborators. “It was like discovering another floor of your house,” says J.J. Abrams. A young James Cameron resolves to quit his job and make a film. In the wake of the film’s release, ILM effectively “ceases to exist,” and the crew scatters to the wind. With the warehouse and equipment on loan from George, John Dykstra forms his own company and begins work on a new space-themed TV show, Battlestar Galactica. “I wanted to keep that place and I wanted to keep those people,” he tells us. But when George comes calling with an offer to move to Northern California to make a sequel to Star Wars, many find themselves facing the painful decision to leave Dykstra, who has not been invited. “It was like breaking up a family,” Joe Johnston recalls. As work begins at the new Kerner facility in Marin County, the returning ILM team finds their “reputations on the line,” as they attempt to top the most successful film of all time. Richard Edlund designs and builds a completely new optical printer, determined to “conquer the evil matte line.” And a US Steel brochure inspires Joe Johnston to design four-legged tanks. Frustrated with the editing process, George resolves to start a computer division, intent on dragging the film industry into the digital age. He recruits computer scientist Ed Catmull, who dreams of someday using computers to animate a film. George gives him four tasks: digital editing, digital audio, computer graphics, and digital compositing. Meanwhile, the new movie is making extensive use of stop-motion animation and much of the work falls on the shoulders of Phil Tippett. “It was like learning to ride a bike,” Tippett says of the months of practice it took to animate the walkers and the tauntauns. In a captivating personal moment, Tippett shares how the process-oriented nature of the work helped him manage his mental health challenges. George’s unique leadership style comes into focus, as Johnston describes working with George as going to a “fantasy film school that only exists in his head.” When George challenges Dennis Muren to “just think about it,” the moment becomes a life-changing revelation for Muren, who concludes that any problem can be solved with the proper time to contemplate a solution. Harrison Ellenshaw, heading up a matte painting department with ten times the workload of Star Wars, recalls the joys of getting to know “the great” Ralph McQuarrie. Richard Edlund reveals some tricks of the trade, including the clever way he pulled off the shot of the Millennium Falcon blasting off into hyperspace. For prank-loving Ken Ralston, a visit from Walter Cronkite presents a fertile opportunity for goofing off. With the release of the Empire Strikes Back, George encourages ILM to take on outside work for the first time. “Suddenly everyone wants to come to ILM,” Ken Ralston recalls, as the doors open for a set of exciting new challenges.

2. On the Bucking Bronco

No release date yet

As a boy growing up in Modesto, CA in the 1950s, George Lucas develops a fascination with car racing. But when an accident nearly takes his life, teenage George resolves to find his purpose. Bucking his father’s plans for him to take over the family stationery business, George enters film school, where his eyes are opened to the power of cinema. George’s student films garner acclaim and the admiration of contemporaries like Steven Spielberg. When George wins a scholarship to observe filmmaking at Warner Brothers’ Studios, he meets director Francis Ford Coppola, who becomes a close collaborator. Together, George and Francis move to San Francisco to form an independent production company, American Zoetrope. George sets about turning his student film, THX-1138, into a feature, but the final product is deemed incomprehensible by studio executives. Their funding pulled, American Zoetrope goes bankrupt, prompting Coppola to tell George: “No more of this artsy stuff… prove to me that you can do a comedy.” George answers with American Graffiti, a critical and box office smash. But studios are wary of his next idea, a Buck Rogers-style serial set in outer space, full of robots, aliens, and a spaceship-flying dog. Only Fox executive Alan Ladd, Jr. is willing to gamble on George’s wild idea for “The Star Wars.” George hires illustrator Ralph McQuarrie, who brings the imagery of the script to life in stunning detail. And he invests his own money from American Graffiti into a new special effects company he names Industrial Light & Magic. As ILM sets to work on the effects, George has a terrible experience shooting the film in England and Tunisia. When George finally returns to ILM and discovers they have only completed two shots, the stress sends him to the hospital. With just months to go before the film’s release, the ILM team begins to click and makes significant headway. George reshoots the troubled Cantina scene and adorns the memorable Holochess sequence with creatures made by stop motion expert Phil Tippett and his partner Jon Berg. The team then turns their attention to the climactic Death Star Trench Run. With the studio threatening to eliminate the sequence over budget concerns, the ILM team races to the finish. John Dykstra walks us through the process of filming explosions in the Van Nuys parking lot. Their work complete, the ILM team celebrates with a wrap party in the Van Nuys warehouse, where Phil Tippett recalls people “smarter than me” buying 20th Century Fox stock. In May 1977, Star Wars is released, becoming an instant worldwide phenomenon. The ILM team recalls the joy and astonishment of seeing the finished product on the big screen. But despite the film’s success, George remains curiously unsatisfied. Unable to see beyond “the scotch tape and the rubber bands holding it together,” George resolves to “find a better way.”

1. Gang of Outsiders

No release date yet

The year is 1975, and George Lucas has a problem. He envisions his new film as a space opera, full of kinetic movement and speed. But with no special effects company in Hollywood capable of tackling his massive vision, George’s only choice is to start his own. Enter John Dykstra, camera expert, machinist, motorcyclist, pilot. Dykstra begins assembling an unlikely team of artists, builders, and dreamers to join the newly christened Industrial Light and Magic. Setting up shop in an empty warehouse in Van Nuys, Dykstra puts in a call to camera operator Richard Edlund, whose colorful resume includes a stint in the Navy, rock and roll photography, cable car operator, and the invention of a popular guitar amplifier. Meanwhile, a job posting for a “space movie” catches the eye of a young artist named Joe Johnston, who is desperate to cut down his commute time. The ensuing six-week offer to do storyboards is only complicated by the fact that Joe has no idea what a storyboard is. News of the science fiction project in Van Nuys also attracts the interest of young effects enthusiasts Dennis Muren, Ken Ralston, and Phil Tippett. Admirers of Ray Harryhausen, all three have been making films since childhood. Upon reading the script for “The Star Wars,” Ralston marvels at the opportunity. Muren, however, simply thinks, “this is impossible.” This “cabal of secret special effects people,” as George describes them, will prove uniquely suited to the task at hand. “I think he wanted a bunch of guys who didn’t know what was impossible,” says Joe Johnston. Under John Dykstra’s leadership, the team sets to work creating a complex motion control system to allow the camera to repeat movements, a prototype of which Dykstra had pioneered in a series of experiments at the University of Berkeley. As the months roll on, the team puts in eighteen-hour days at the warehouse in hundred-degree heat, occasionally letting off steam through slip n’ slide parties in the parking lot. Newly hired industrial designer Lorne Peterson blows the minds of his fellow model makers with a revolutionary new adhesive called superglue. “We were flying by the seat of our pants in a lot of ways,” Edlund recalls. For matte painter Harrison Ellenshaw, the culture shock of working at Disney by day and the ILM warehouse at night was jarring: “At Disney I was one of the youngest people, at ILM I was an old guy.” Six months in, designing and building everything from scratch has proved much harder than anyone anticipated. The motion control prototypes are now complete, but the team has yet to produce a single piece of finished film. “We built this violin and now we had to learn how to play it,” Edlund explains. As principal photography wraps in England, the team scrambles to finish what they can. George returns to ILM, worn down by the stress of shooting, to find his team has only completed two shots out of the roughly four hundred needed. “I was… not happy,” George tells us.